Alberta oil refinery operating for years without provincial approval faces enforcement order

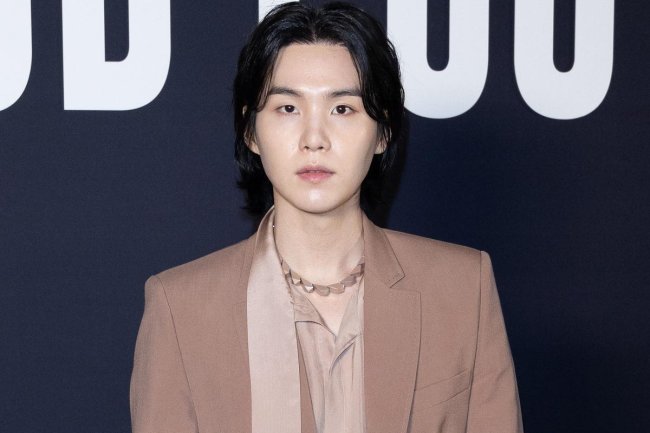

A view of the Enerchem plant near Slave Lake, Alta. An enforcement order details how the refinery has operated for years without provincial approval. (Enerchem)A refinery near Slave Lake in northern Alberta is facing an enforcement order for operating without regulatory approval, 22 years after it began processing oil.The Enerchem plant was never granted approval under Alberta's Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act (EPEA), according to the order issued June 20.The order states that no approval "has been issued to any person for the construction, operation and reclamation of the plant," in contravention of the act.Under the conditions set out in the order, the oil fractionation plant, 250 kilometres northwest of Edmonton, can continue operating while the owner, Calgary-based AltaGas, seeks approval from the province.Experts in environmental law say the infraction is troubling evidence of cracks in Alberta's complex regulatory system and undermines its approvals process.Nigel Ba

A refinery near Slave Lake in northern Alberta is facing an enforcement order for operating without regulatory approval, 22 years after it began processing oil.

The Enerchem plant was never granted approval under Alberta's Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act (EPEA), according to the order issued June 20.

The order states that no approval "has been issued to any person for the construction, operation and reclamation of the plant," in contravention of the act.

Under the conditions set out in the order, the oil fractionation plant, 250 kilometres northwest of Edmonton, can continue operating while the owner, Calgary-based AltaGas, seeks approval from the province.

Experts in environmental law say the infraction is troubling evidence of cracks in Alberta's complex regulatory system and undermines its approvals process.

Nigel Bankes, an emeritus professor of law at the University of Calgary, said Alberta Environment needs to assure the public that the plant is in compliance and that other facilities are not operating without oversight.

"The idea of an significant industrial development operating without approval for years, it's off the charts," Bankes said.

"I would describe it as negligence."

Bankes said allowing the company to continue operating, without a proper review, is problematic and assumes the site is in compliance with environmental guidelines.

"We don't know that and we have no means of knowing that."

A question of diligence

According to Alberta Environment, the plant should have sought regulatory approval in 2011, a decade after it was constructed. But legal experts contend the site has been lacking the appropriate regulatory oversight since it began processing oil in 2001.

It isn't clear how the infraction went undetected for years, or what environmental oversights were in place during the lapse.

The enforcement order, which expires in June 2024, says the owner must undertake a series of compliance conditions, including environmental monitoring for water, air, soil and emissions.

The order also outlines requirements for a reclamation plan, record-keeping, and monthly and annual reporting.

Jason Unger, executive director of Edmonton's Environmental Law Centre, said the order calls into question the strength of Alberta's regulatory system and Alberta Environment's role as a watchdog for the industry.

He said no hearing was ever held to determine the overall impact of the operation, and that attempting to enforce oversight of environmental guidelines after the fact is ineffective.

"You have to question the diligence of compliance overall," Unger said. "It's problematic from a robust regulatory perspective in terms of managing risks and understanding what those risks are."

The plant, about 10 kilometres north of the town of Slave Lake, relies on fractionation, the distillation process that oil refineries use to separate crude oil into more useful products.

It produces hydrocarbon fluids for fracturing and drilling of oil and gas wells, along with various consumer fuels including furnace fuel, diesel and specialized jet fuels.

The refinery was built in 2001. When the $9-million project was announced, the plant was expected to be on stream by November of that year, producing 6,000 barrels of refined products per day.

Differing accounts

Government and company officials offer differing accounts of how approval for the refinery was overlooked, and for how long.

AltaGas says confusion surrounding who has regulatory jurisdiction over the operation is to blame. The company and Alberta Environment both point to historic changes in regulatory laws.

Experts say their justifications fail to account for a violation of legislation that has been in force for decades.

CBC News is awaiting comment from the federal government and Environment Canada.

An AltaGas year-end report issued in February 2021 said the refinery would be added to the AltaGas portfolio through the company's acquisition of a controlling interest in Petrogas Energy Corp.

After AltaGas became the owner of the Slave Lake refinery in 2022, it informed the government that it had no provincial approval, according to Alberta Environment.

"As soon as we were alerted to the facility's current operations, the department took action," Tom McMillan, director of communications for Alberta Environment, said in a statement.

The ministry is working with the refinery to ensure it complies with the "strict conditions" of the order, McMillan said. He said "formalized and mandatory notification processes" are now in place to ensure regulatory oversight is maintained following legislative or operational changes.

"Operators of all facilities are accountable for ensuring that they are operating with all current regulatory approvals at any given time," McMillan said.

"While the previous owner failed in this regard under EPEA, to the best of our knowledge, the company continued to comply with the various regulatory expectations for an oil fractionating facility under the Alberta Energy Regulator during this time."

Asked by CBC if it ever monitored the plant, including its environmental impact, the AER confirmed that it does not regulate oil refineries. Under the EPEA, Alberta Environment is responsible for regulating oil refineries.

Watchdog questions

Alberta Environment said the refinery was originally authorized under the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board, prior to construction in 2001. The board replaced that authorization with an industrial development permit the following year, Alberta Environment said.

After the Energy Resources Conservation Board replaced the EUB in 2008, the act was changed. In 2011, requirements for industrial development permits were removed from the legislation. When the permits were removed, the facility "was left without the approvals required for operation," Alberta Environment said.

A spokesperson for AltaGas said the Slave Lake facility was in full compliance with existing regulations when it started operating in 2001.

"As regulations and regulatory bodies have changed since operations began, we have and will continue to work collaboratively with our regulators to ensure we continue to operate in compliance," the company said.

"The Slave Lake facility was recently interpreted to be included within the definition of an oil refinery, which would place it under the jurisdiction of Alberta Environment and Protected Areas."

Permit implications

Bankes said Alberta Environment's reference to industrial development permits is an attempt to deflect blame. Repealing the permits did not alter the operation's status in a material way, he said.

The permits were never intended to supersede the need for broader approval under the act, Bankes said.

The refinery should have always sought approval under the act, he said.

"The repeal of the development permit provisions of the act shouldn't have created a gap in the environmental approvals process," he said. "It should have been Alberta Environment all along."

Alberta's environmental protection act has been in place since 1992. The operation should have sought approval under that legislation before construction commenced, Bankes said.

"If you're running a refinery, you're presumably putting out some pretty nasty stuff into the atmosphere, so you'd need an air-quality approval and all sorts of things like that," he said.

"The industrial development permits never, ever dealt with that aspect of an operation."

Unger said the company's reference to the plant being "recently interpreted" as an oil refinery also raises questions of accountability.

Under the EPEA, designated activities require approval and oil refineries have been on that list for decades.

The definition of an oil refinery — "a plant for manufacturing hydrocarbon products from oil, heavy oil, crude bitumen or synthetic crude oil" — has remained unchanged since 1996.

Unger said the fact the company has operated for so long without approval undermines the discretion of regulators to reject the project.

Much of the language in the enforcement order mimics the requirements of an operational approval document, he said.

"Perhaps more problematically, the monitoring and reporting and the emission standards that are embedded in the conditions of the enforcement order — we don't know if those were ever complied with."

Somebody obviously dropped the ball.- Murray Kerik

Murray Kerik, reeve of the Municipal District of Lesser Slave River, said local government was not informed of the infraction. Council will contact Alberta Environment for further clarification about what went wrong, he said.

Kerik said his community is open to industry, and is not aware of any issues at the plant over its decades of operation, but it's concerning that proper oversight was not in place.

"You hope they're following all the rules and regulations. But is that not where Alberta Environment is supposed to be the watchdog?

"Somebody obviously dropped the ball."

What's Your Reaction?