Missouri Supreme Court Upholds Law That Allows Jailing Parents of Truant Children

State law requires ‘regular’ attendance but doesn’t define what that means The court’s decision comes as school attendance rates have fallen since the pandemic, and as math and reading scores have dropped. Photo: Neeta Satam for The Wall Street Journal By Shannon Najmabadi Aug. 15, 2023 4:19 pm ET The Missouri Supreme Court on Tuesday upheld a law that allows parents to be jailed if their children don’t attend school regularly, which the court defined as every day class is in session. The litigation centered on two single mothers in Lebanon, Mo., who were sentenced to jail after their elementary-school-age children each missed about 15 days of class in the 2021-22 school year. The mothers called in to explain some of the absences, but officials at the Lebanon R-III School District, a so

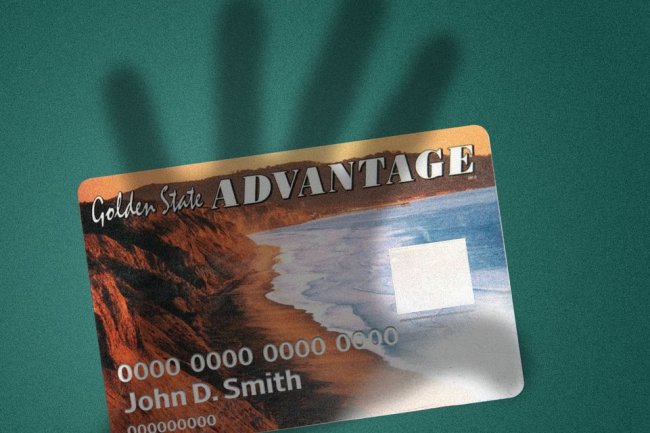

The court’s decision comes as school attendance rates have fallen since the pandemic, and as math and reading scores have dropped.

Photo: Neeta Satam for The Wall Street Journal

The Missouri Supreme Court on Tuesday upheld a law that allows parents to be jailed if their children don’t attend school regularly, which the court defined as every day class is in session.

The litigation centered on two single mothers in Lebanon, Mo., who were sentenced to jail after their elementary-school-age children each missed about 15 days of class in the 2021-22 school year. The mothers called in to explain some of the absences, but officials at the Lebanon R-III School District, a southwestern Missouri district with about 4,500 students, referred both to prosecutors.

The district’s handbook, which parents must acknowledge reading, says students should maintain an attendance rate of at least 90% to prepare children for adulthood and professional life and ensure continuity of learning.

State law, however, is more vague.

Missouri’s compulsory education statute requires children to attend school on a “regular basis,” which attorneys for the Lebanon mothers argued is unconstitutionally vague.

The mothers weren’t told that illnesses, even when called in by a parent, were counted as unverified absences unless a doctor’s note was presented, their attorneys argued.

“Lot of you all have had kids in school. Nobody thinks that they are going to be prosecuted for this,” said Ellen Flottman, the appellate public defender who argued the two mothers’ cases before the state Supreme Court.

The Missouri Attorney General’s office said that even minor offenses are violations of the law, and that the school district followed up with the parents as absences accrued.

In its decision, written by Judge Robin Ransom, the court said that based on common understanding, “no Missouri parent would conclude attendance ‘on a regular basis’ means anything less than having their child go to school on those days the school is in session.”

The court acknowledged the implication of its decision “if taken to the extreme” but said prosecutors and school officials have discretion not to enforce marginal cases.

“This Court is bound by its duty ‘to ascertain the intent of the legislature from the language used and to consider the words used in their plain and ordinary meaning,’” Ransom wrote.

Five Supreme Court judges concurred with Ransom. A final judge didn’t participate.

The decision comes as school attendance rates have plummeted since the Covid pandemic, and as U.S. students’ math and reading scores have dropped, according to federal data.

Chronic absenteeism—which most education experts equate to missing about 18 days in a 180-day school year—disrupts learning for students and their peers, if teachers frequently need to revisit past material.

Absenteeism can be driven by a number of factors, said Robert Balfanz, a research professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Education. Students might not want to go to school because they are being bullied or are disengaged academically. Middle and high-schoolers can leave campus after their parents drop them off. Poverty and lack of resources—which can lead to unstable transportation, unpredictable work schedules or children caring for siblings—are also correlated with chronic absenteeism, Balfanz said.

“You have parents who themselves didn’t have great experiences in school, so may not be the best advocates for their children about the importance of an education,” said Jessica Pennington, the former executive director of the Truancy Intervention Project in Atlanta, Ga.

Experts in education law or absenteeism say there is no one solution to address truancy given the variety of causes. However, most say motivating attendance is more effective than handing out penalties.

Maura McInerney, who has represented many families facing truancy charges through her work as legal director of the Education Law Center, said penalties can cause friction between families and the school, which can make students more disengaged.

“They’re afraid of fines and they are afraid of what will happen,” she said of the families.

More than 40 states have some kind of truancy statute that penalizes parents or students for chronic absenteeism, through penalties that can include fines, jail time, taking driver’s licenses or referrals to child-welfare agencies.

In recent years, some states have modified those laws or introduced diversion programs in light of cases in which, for example, a parent died in jail or school districts or courts were found to benefit financially from the fines paid.

Madeline Sieren, a spokeswoman for the attorney general’s office, said “we’re pleased with the Court’s decision, as it recognized the importance of education for Missouri’s children.”

Jacy Overstreet, a district spokeswoman, previously said the district involves the court system as a last resort. She did not immediately respond to a request for comment Tuesday.

Flottman declined to comment.

Write to Shannon Najmabadi at [email protected]

What's Your Reaction?