Texas May Execute a Man Based on a Scrapped Medical Theory

Autistic father Robert Roberson was wrongfully convicted of murdering his 2-year-old daughter. By John Grisham Sept. 7, 2023 6:02 pm ET Robert Roberson with Nikki Photo: Courtesy of Robert Roberson Family For a parent, nothing is worse than the death of a child. Imagine the horror, though, of being falsely accused and wrongly convicted of killing your child. Twenty years ago, prosecutors in Anderson County, Texas, relied on a now-discredited hypothesis about “shaken baby syndrome” to convict Robert Roberson of the capital murder of his chronically sick 2-year-old daughter Nikki. Countless caregivers have been prosecuted since British pediatrician Norman Guthkelch first posited in the early 1970s that shaking a baby could cause brain bleeding and even death. Many have been convicted and sent to

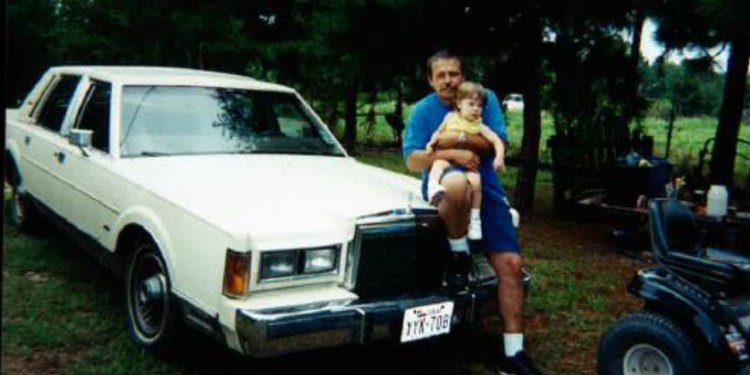

Robert Roberson with Nikki

Photo: Courtesy of Robert Roberson Family

For a parent, nothing is worse than the death of a child. Imagine the horror, though, of being falsely accused and wrongly convicted of killing your child.

Twenty years ago, prosecutors in Anderson County, Texas, relied on a now-discredited hypothesis about “shaken baby syndrome” to convict Robert Roberson of the capital murder of his chronically sick 2-year-old daughter Nikki. Countless caregivers have been prosecuted since British pediatrician Norman Guthkelch first posited in the early 1970s that shaking a baby could cause brain bleeding and even death. Many have been convicted and sent to prison, a few even to death row. Mr. Roberson could be the first to be executed. Texas may execute an innocent man.

Mr. Roberson has autism and was a special-education student before dropping out of school in the ninth grade. He had his challenges in life, including past drug addiction that had prompted convictions for writing a hot check and burglary. But he loved being a father to Nikki.

She, too, had her challenges. Child Protective Services forced Nikki’s mother to give her up at birth. Nikki suffered from chronic and severe middle-ear infections. In late January 2002, she had a high fever and undiagnosed pneumonia. Mr. Roberson put Nikki to bed but awoke later and found her on the floor. Mr. Roberson told police that Nikki didn’t appear to have any injuries. She was awake and talking as he tried to soothe her. Father and daughter managed to get back to sleep, but the next morning Nikki was unresponsive. Mr. Roberson brought her to an emergency room in Palestine, Texas. He told hospital staff that she had fallen out of bed, but they didn’t believe him. They didn’t know he was autistic and decided he didn’t show the proper emotions given the dire situation. Doctors transferred Nikki to a children’s hospital in Dallas, but it was too late. She died on Feb. 2.

Mr. Roberson was distraught but his nightmare was only beginning. The Anderson County District Attorney’s Office accused him of killing Nikki and sought the death penalty.

The deck was stacked against Mr. Roberson from the beginning. Accepted medical wisdom at the time was that any child with a triad of symptoms like Nikki’s—brain bleeding, brain swelling and bleeding in the eyes—had been violently shaken or hit against a surface, absent evidence of some other massive trauma such as a car accident or a multistory fall. The medical consensus viewed the presence of the triad to be diagnostic and considered the caregiver the culprit.

In a rush to judgment that is the hallmark of wrongful convictions, one doctor’s hunch about Nikki’s death led to Mr. Roberson’s arrest for murder. Even Mr. Roberson’s court-appointed lawyer agreed this was a “classic” shaken-baby case because, 20 years ago, the triad was considered diagnostic.

Astonishingly, a nurse claimed to law enforcement—and later in front of the jury—that Nikki had been sexually abused, even though no doctor endorsed that belief and there was no autopsy or crime scene evidence of it. The judge allowed the nurse’s testimony and prosecutors’ argument that Mr. Roberson was the kind of person capable of violently shaking a child to death. The jury agreed.

Dr. Guthkelch eventually became distressed at the aggressive misuse of his work by prosecutors. “I am frankly quite disturbed that what I intended as a friendly suggestion for avoiding injury to children has become an excuse for imprisoning innocent people,” he said in 2012 while arguing that convictions like Mr. Roberson’s should be reviewed. “We went badly off the rails.”

Slowly, belatedly, things are changing. Courts in 17 states have exonerated people convicted decades ago of murder or child abuse based on the outdated shaken-baby hypothesis. In 2016, days before Mr. Roberson was set to die, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals returned his case to the trial court for an exhaustive 10-day hearing. Mr. Roberson’s legal team presented six experts who showed that the outdated version of shaken-baby syndrome used at his trial has been discredited and that Nikki died as a result of her undiagnosed pneumonia, medications and accidental fall.

To overturn his conviction, Mr. Roberson’s lawyers had to accomplish two things. First, they had to show that the science used to convict him was wrong (or that the understanding of that science had changed since his trial). Second, they needed to demonstrate that the original jury wouldn’t have convicted him if it knew then what we know now about the shaken-baby syndrome hypothesis. Mr. Roberson’s legal team did more than those two things: It produced unrebutted evidence that no homicide had in fact occurred.

Mr. Roberson’s lawyers presented a 302-page document to the court that comprehensively summarized the new evidence from the experts. Anderson County prosecutors submitted a 17-page brief that hardly touched on the new science—instead rehashing outdated evidence and theories from the original trial in 2003. Mr. Roberson’s lawyers were surprised at the paltry offering. They were flabbergasted when Judge Deborah Evans

rubber-stamped it, following the prosecution’s lead in ignoring most of the new expert testimony and all of the scientific studies showing a change in understanding of shaken-baby syndrome. Instead, the trial court’s recommendation cited the same trial testimony that had been challenged as wholly inconsistent with contemporary scientific understanding.We expect our courts to weigh the evidence before them carefully and thoughtfully. But in Mr. Roberson’s case, and in a shocking number of wrongful convictions, judges simply agree with prosecutors and protect bad convictions despite overwhelming evidence of innocence. We should demand more from judges than a copy-and-paste job that entirely ignores changes in the scientific understanding of a case, especially when a life is on the line.

Nikki’s death was a tragedy, not a crime. Robert Roberson may be out of options unless the U.S. Supreme Court decides to hear his case.

Mr. Grisham, a novelist, serves on the boards of the Innocence Project and Centurion Ministries, organizations dedicated to exonerating defendants who were wrongfully convicted.

Journal Editorial Report: The week's best and worst from Bill McGurn, Kate Bachelder Odell, and Kyle Peterson. Images: AP/Zuma Press Composite: Mark Kelly The Wall Street Journal Interactive Edition

What's Your Reaction?