‘The Oldest Book in the World’ Review: Also Sprach Ptahhatp

A set of maxims attributed to an adviser of an Egyptian pharaoh may be the world’s earliest surviving work of philosophy. Facsimile from the Papyrus Prisse. Photo: Imagebroker/Bridgeman Images By Dominic Green July 6, 2023 6:20 pm ET In 1847 the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris acquired a 16-page scroll from the antiquarian Émile Prisse d’Avennes (1807-1879). He had bought it from one of the local men then excavating a cemetery near a pharaonic temple complex at Thebes in Egypt. The Papyrus Prisse, as it is known, contains the only complete version of a set of philosophical epigrams called “The Teaching of Ptahhatp.” Recognized upon its publication in 1858 as “the oldest book in the world,” the “Teaching” is attributed to a vizier to Izezi, the eighth and penultimate pharaoh of the Old Kingdom’s Fifth Dynasty, who ruled Egypt i

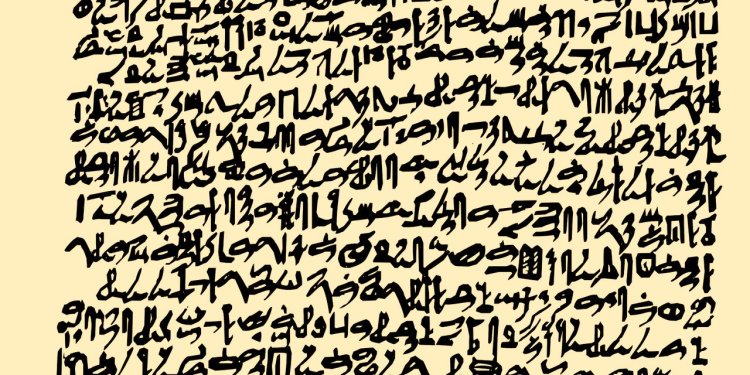

Facsimile from the Papyrus Prisse.

Photo: Imagebroker/Bridgeman Images

In 1847 the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris acquired a 16-page scroll from the antiquarian Émile Prisse d’Avennes (1807-1879). He had bought it from one of the local men then excavating a cemetery near a pharaonic temple complex at Thebes in Egypt. The Papyrus Prisse, as it is known, contains the only complete version of a set of philosophical epigrams called “The Teaching of Ptahhatp.” Recognized upon its publication in 1858 as “the oldest book in the world,” the “Teaching” is attributed to a vizier to Izezi, the eighth and penultimate pharaoh of the Old Kingdom’s Fifth Dynasty, who ruled Egypt in the late 25th and early 24th centuries B.C.

Bill Manley, who taught Ancient Egyptian and Coptic languages for decades in British universities, has made a new translation. In “The Oldest Book in the World,” he claims Ptahhatp as the first philosopher, and places the “Teaching” alongside, or rather, long before, “more recent classics” such as Lao-Tzu’s “Tao Te Ching,” Plato’s “Republic,” and the “Meditations” of that latecomer Marcus Aurelius. But then, every writer is a latecomer if Mr. Manley is right.

At the age of 110, Ptahhatp’s eyesight and hearing are weakening, his bones ache and his nose is blocked. It is time for the “Overseer of the City” to bequeath “historic words” as “a model for the children of responsible people.” Rather than draw hieroglyphs as we might imagine, he writes in “hieratic,” a cursive, joined-up script. He writes from right to left without vowels; Ancient Egyptian, one of whose dialects survives in the liturgy of the Coptic Church, has affinities with Hebrew and Berber.

As a lifelong servant of a god-king, Ptahhatp has developed a certain patience. Experience teaches philosophical self-regulation. Do not tarry with fools or feed the troll: “As your reputation is immaculate, you need not speak.” “No one will be born wise,” so “consult with the simple” as much as the educated: “Wise words are rarer than malachite yet found among the girls at the grindstones.” Remember your table manners, contain your temper and “remove yourself from any misconduct.” Your children are “the outpouring of your spirit,” so don’t “take them for granted.” Gossip is a “ruination from fantasy,” true friendship is the “spirit that brings gladness.”

Tombs at the royal cemetery of Saqqara, near Cairo, show that five Ptahhatps were viziers to the Fifth and early Sixth Dynasties. One was Izezi’s first vizier, the putative author of the “Teaching.” His grandson, the second Ptahhatp, was Izezi’s last vizier. These two Ptahhatps are buried near Izezi, but the third and fourth Ptahhatps are buried elsewhere at Saqqara near earlier kings. The relationship between these two pairs and a fifth Ptahhatp who is buried in a third location is unclear. High office was often inherited along with names, Mr. Manley notes, so all these Ptahhatps “could well be members of the same family.”

The Papyrus Prisse dates from the late 18th or early 17th century B.C., about 200 years into Egypt’s Middle Kingdom era. This was around 700 years after the death of the first Ptahhatp. That lapse of time is roughly the same as that between the Exodus from Egypt and the redaction of the Torah, or a bit more than half the time that passed between the Trojan Wars and the Homeric account. Does the “Teaching” preserve revered insights or is it a later construction—or does it combine elements of both?

Mr. Manley detects traces of Old Kingdom phrasing and a consistent Middle Kingdom grammar, and he cites the copying and popularity of the “Teaching” in the Middle Kingdom. His crisp translations are suggestive of the ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian traditions of wisdom literature, as well as more recent classics such as Castiglione’s “Book of the Courtier,” the ruminations of Polonius in “Hamlet” and Jordan Peterson’s “12 Rules for Life.”

Like Plato in Robin Waterfield’s 1994 version of “Gorgias,”Mr. Manley’s Ptahhatp speaks our language. Where Mr. Waterfield brought out the colloquial note of conversation (“You don’t know the half of it, Socrates!”), Mr. Manley accentuates the poetic. Pederasty is wrong because the young are “the fluid-at-heart.” “What will be will be” is easier on mortals than the literal “No one can escape what is fated for him.” You might as well “Smile all the time of your being.”

The “Teaching,” Mr. Manley writes, contains more than Machiavellian strategies, relationship advice, and tips for winning friends and influence in an era of bureaucratic despotism and monumental pyramids. Ptahhatp addresses the unchanging realities of politics, family and friendship within another, less tangible reality, the mutable metaphysical framework in which we understand our lives. This, Mr. Manley argues, makes the “Teaching” not just “the earliest complete statement of philosophy surviving from ancient Egypt,” but also “the oldest surviving philosophy book from anywhere in the world.”

“Ideal is the listening and ideal the speaking of all who have heard what transforms,” Ptahhatp tells us. His goal is merut nefret, which Mr. Manley translates as “wanting wisdom” or “wanting the ideal,” anticipating the literal meaning of “philosophy” in Greek, as well as the metaphysics of Plato’s idealism. Herodotus reported that the Egyptians were “the first of all men on earth” when it came to observing the sun, assembling a divine pantheon, building temples and engraving “figures on stones.” In Mr. Manley’s adroit and pioneering translation, the “Teaching” is philosophy ages before the Greeks had it. “True integrity gets passed on.”

Mr. Green is a Journal contributor and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

What's Your Reaction?