Turkey’s Double Dealing in the Ukraine War

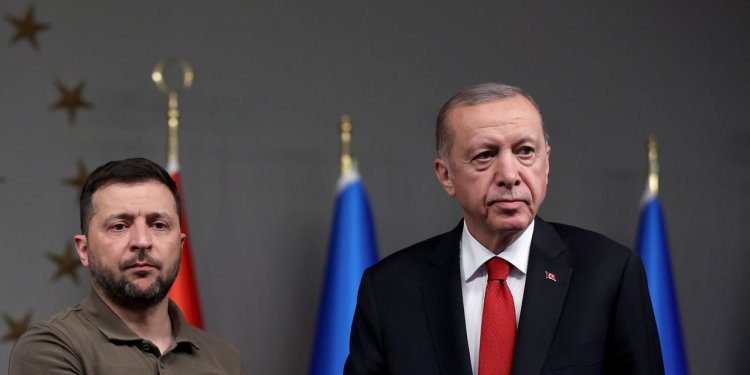

Though Ankara has provided help to Kyiv, its real aim is to prolong a conflict that extends its regional influence and diplomatic clout Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky (left) with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan after their meeting in Istanbul on July 7. Photo: Tolga Bozoglu/Zuma Press By Michael Kimmage and Hanna Notte July 13, 2023 2:38 pm ET At the last minute, Turkey gave a gift to NATO, whose members gathered in Vilnius this week for a much-anticipated summit. It dropped its objections to Sweden’s entry into the alliance, confirming NATO’s transformation after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Not only have NATO member states given a remarkable amount of military aid to Ukraine. The alliance itself has grown to include Finland and will soon include Sweden, two affluent democracies that will stre

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky (left) with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan after their meeting in Istanbul on July 7.

Photo: Tolga Bozoglu/Zuma Press

At the last minute, Turkey gave a gift to NATO, whose members gathered in Vilnius this week for a much-anticipated summit. It dropped its objections to Sweden’s entry into the alliance, confirming NATO’s transformation after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Not only have NATO member states given a remarkable amount of military aid to Ukraine. The alliance itself has grown to include Finland and will soon include Sweden, two affluent democracies that will strengthen NATO.

Turkey, a crucial supplier of drones to Ukraine throughout the war, has recently been sending signals of encouragement to Ukraine. Having just hosted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Istanbul, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has stated that Ukraine deserves to be in NATO once the war is over. To Russia’s irritation, Turkey allowed commanders from the controversial Azov brigade to return to Ukraine after they had been released from Russian captivity in a prisoner swap. Meanwhile, Baykar, a Turkish company, has begun building a plant for drone production in Ukraine.

Yet it would be a mistake to interpret Turkey’s actions as emphatic support for Ukraine. The U.S. and its most important allies on Ukraine—France, Britain, Germany and Poland—believe that Russia’s invasion was entirely unjust. They hope either for a complete restoration of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territory or for Russia to lose the will to fight because of the invasion’s increasing costs.

“Turkey has maneuvered the international landscape in such a way as to make itself more powerful. ”

Turkey does not share this approach. Before Russia’s invasion in February 2022, Turkey had imperfect but functional relations with Europe. Its EU ambitions had been stalled for a while. Whereas the EU wanted an end to the civil war in Syria, Turkey joined the war for the sake of diminishing Kurdish influence. Still, Turkey helped to broker a deal on the 2015 migrant crisis, whereby European governments paid Turkey to house refugees.

Prior to February 2022, Turkey’s real problem was with the U.S. As Ankara saw it, the Americans had destabilized the region around Turkey by waging war in Iraq. To deal with the ensuing spread of terrorism, the U.S. was cooperating with various Kurdish groups, crossing a Turkish red line. To the enormous discontent of Erdogan, Washington also refused to hand over Fethullah Gulen, a political figure living in exile in the U.S. and linked to the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey. Erdogan did not just have a handful of policy disagreements with the U.S. He felt himself to be at cross-purposes with Washington.

Erdogan (left), appears with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg (center) and Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson in Vilnius, Lithuania on Monday. Erdogan dropped his objections to Sweden joining the alliance one day before NATO’s summit in Vilnius.

Photo: Filip Singer/Press Pool

Erdogan expressed his frustration by drawing closer to Russia. He and Putin never found it effortless to cooperate, and they clashed at times over Syria, Libya and the South Caucasus. But they saw value in coordinating their activities diplomatically and on the ground, sidelining Western actors in the process. Erdogan and Putin connected Turkey’s and Russia’s economies through gas deals, tourism and the construction of the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant by Russia’s Rosatom. Turkey’s purchase of air-defense systems from Russia highlighted their military integration. The outrage in Washington was so great that the U.S. blocked Turkey from gaining access to some American military technology.

When Russia invaded, Turkey could appear to side with Ukraine. Turkish Bayraktar drones became so instrumental to the Ukrainian war effort that Ukrainians started naming their children Bayraktar. Turkey also functioned as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia, hosting talks between the two countries in the first few weeks of the war, while later facilitating negotiations on a range of technical problems related to the war, including the Black Sea grain initiative and security arrangements for Ukraine’s nuclear power plant in Zaporizhzhia.

“Turkey has been a release valve for Russia, lessening its international isolation.”

Turkish assistance to Ukraine was welcomed by the U.S. and its European allies. But Turkey in no way distanced itself from Russia. In fact, Turkey has been a key contributor to Russia’s war effort. It has shown that not even every NATO member is implacably opposed to Russia’s war. Since the conflict began, Russian tourists and businesses have had a hard time operating in the EU. By contrast, Turkey has been a release valve for Russia, lessening its international isolation. This is of both practical and symbolic help to Russia.

Turkey’s most consequential aid to Russia has come through the circumvention of sanctions. Turkey has become—together with Georgia, Armenia and countries in Central Asia—a staging ground for the “roundabout trade,” the transit of sanctioned goods into Russia. Some of these goods have both civilian and military purposes, making it easier for Russia to prosecute its war against Ukraine. At the same time, through its official stance on the war, Turkey positions itself as a peacemaker, reaping reputational benefits.

The Turkish and Russian economies are linked through projects including the construction of Ukraine’s Akkuyu nuclear power plant by Russia’s Rosatom.

Photo: ozan kose/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Turkey has devoted itself to preventing a Russian victory. A successful expansionist Russia would threaten Turkey. Turkey has simultaneously undermined the prospects of a decisive Ukrainian victory, since it might bring about Putin’s fall, depriving Erdogan of a crucial partner. A Russia that is distracted in Ukraine is less and less able to strong-arm Turkey economically or to exert its will in Turkey’s neighborhood. A diminished Russia has fewer cards to play against Turkey in Syria and limited capacity to bolster Armenia against Azerbaijan, Turkey’s ally. This is the kind of Russia that Erdogan wants. He hopes for a long, inconclusive war in Ukraine.

Rather than pay a price for prolonging and exploiting Russia’s war for its own ends, Erdogan got the NATO alliance to dance for months around his preferences. How the U.S. managed to elicit his support for Sweden’s membership will be clarified over time. No doubt, though, it was by giving Turkey something, and this is the precedent Erdogan has set in Vilnius. Nor could the U.S. and other NATO members who truly back Ukraine have done otherwise. They had to massage Turkish interests to get Sweden into the alliance, which will be a boon to Sweden and a boon to the alliance. As far as NATO members are concerned, Europe will become more secure.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How do you view Turkey’s role in NATO? Join the conversation below.

The loser in this turn of events is Ukraine. The war has shown that when NATO wishes, it can bring in new members, but these new members are Sweden and Finland. Ukraine’s path toward NATO membership, as the alliance again made clear, will be long and arduous. The process will avoid drawing NATO more deeply into what could be a long stalemate with Russia. For its part, Turkey has maneuvered the international landscape in such a way as to make itself more powerful. It is the only country in the world that has substantial leverage within NATO, a robust relationship with Ukraine and a robust relationship with Russia. It occupies a privileged position.

Because Turkey is acquiring greater international stature from the war, it is all the more important to pay close attention to its position on the war. Turkey is no friend of the U.S. and no friend of Russia. And in Ukraine’s hour of need, it is also no true friend of Ukraine’s. It will continue to use its expanding regional influence and diplomatic clout to prolong the conflict and complicate Kyiv’s march toward victory.

Michael Kimmage is a professor of history at Catholic University and from 2014 to 2016 held the Russia/Ukraine portfolio on the policy planning staff at the U.S. State Department. Hanna Notte is a senior research associate at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Nonproliferation.

What's Your Reaction?