Milan Kundera was a writer of caustic irony and mordant wit

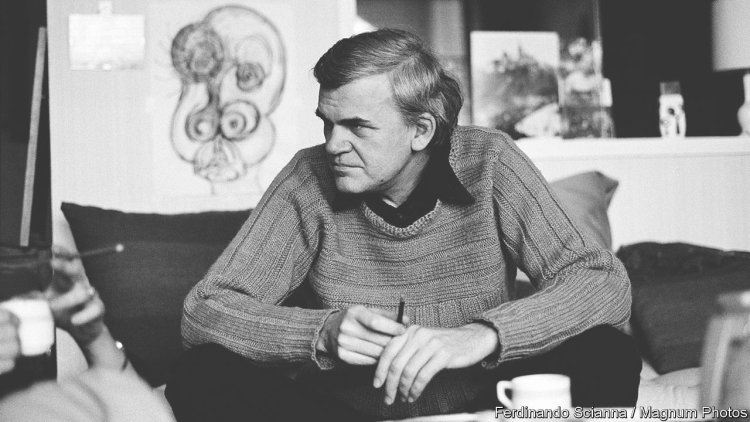

image: Ferdinando Scianna / Magnum PhotosIN MILAN KUNDERA’S most famous novel, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, a dissident Czech artist feted in Germany finds herself lauded as a “saint or martyr”. Sabina protests, however, that her “enemy is kitsch, not Communism!” Mr Kundera, who died on July 11th aged 94, moved from a fervent youthful socialism to global renown as an exiled author who dissected and derided the follies and cruelties of the Soviet satellite regime that ruled his homeland until 1989. He insisted always, though, on the supremacy of art over any ideology, and championed the novelist’s vocation in an era “befogged with ideas and indifferent to works”. For Mr Kundera, the deadly foe of truthful art was kitsch: the narcissistic sentimentality that, under any social system, effaces realities and encourages people to “gaze into the mirror of the beautifying lie”. With caustic irony, mordant wit and acrobatic literary skill, he mocked the beautifying lie wherever he found

IN MILAN KUNDERA’S most famous novel, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, a dissident Czech artist feted in Germany finds herself lauded as a “saint or martyr”. Sabina protests, however, that her “enemy is kitsch, not Communism!” Mr Kundera, who died on July 11th aged 94, moved from a fervent youthful socialism to global renown as an exiled author who dissected and derided the follies and cruelties of the Soviet satellite regime that ruled his homeland until 1989. He insisted always, though, on the supremacy of art over any ideology, and championed the novelist’s vocation in an era “befogged with ideas and indifferent to works”.

For Mr Kundera, the deadly foe of truthful art was kitsch: the narcissistic sentimentality that, under any social system, effaces realities and encourages people to “gaze into the mirror of the beautifying lie”. With caustic irony, mordant wit and acrobatic literary skill, he mocked the beautifying lie wherever he found it—in politics, in culture or in personal relationships. Before and after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, Mr Kundera became one of the world’s best-known critics of the abstract idealism that can lead to tyranny. In agile, fragmentary, essay-like fictions, he took aim at the belief in history as a progressive “Grand March” towards “brotherhood, equality, justice, happiness”.

Yet his scorn for “totalitarian” idealists had its roots in his experience as one of them. Born in Brno in 1929 as a musician’s son, he studied literature in Prague; as communists took power in 1948, he produced poetry to glorify their revolution. “I too once danced in a ring,” he writes in “The Book of Laughter and Forgetting”. He too felt “the magic qualities of the circle”.

Soon, the circle broke. A gag that went wrong, commemorated in “The Joke”, led to his expulsion from the party in 1950. Although he returned to party loyalty for a while, and taught literature to film students in Prague, “The Joke”—published in 1967, then banned—set him on the road to official disgrace, dissidence and exile. Having understood “what it is for a man to live through the death of his nation” after the Soviet invasion in 1968, he lived in France from 1975. Later, he would write in French.

Playful, elusive, experimental, Mr Kundera eschewed not just the “Grand March” but the grand statement. “My lifetime ambition,” he told the Paris Review, “has been to unite the utmost seriousness of question with the utmost lightness of form.” Music, his first love, gave him a model. His novels consist of sets of variations (often in seven parts) composed in the vein he admired in the greatest central European writers: “the privileged sphere of analysis, lucidity, irony”.

After his breakthroughs with “The Book of Laughter and Forgetting” (1979) and “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” (1984), readers and writers around the world—from Philip Roth to Salman Rushdie—found in Mr Kundera a liberating inspiration. Sceptics deemed him chilly, manipulative, aloof. His cold-eyed, even abrasive, appraisal of both women’s and men’s romantic lives brought charges of misogyny. He revelled in not only “the undiscovered comic side to history” but also “the (hard-to-take) comic side of sexuality”.

Although later novels—he wrote ten—shrank in size and impact, he kept faith with the art of fiction. For Mr Kundera, the novelist is “neither historian nor prophet” but “an explorer of existence”. Fiction preserves reality in an age of oblivion, since “the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” And humour gives fiction its resilience: not just funny turns, but an “unobtrusive light” that “glows over the vast landscape of life”. Its mortal foe, both in communist and consumerist society, will always be the dishonesty and phoney solidarity of kitsch. Against humourless sentimentalists and ideologists, novelists opened a realm of freedom and tolerance, Mr Kundera thought: a place “where no one owns the truth and everyone has the right to be understood.” ■

For more on the latest books, films, TV shows, albums and controversies, sign up to Plot Twist, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter

What's Your Reaction?