Richard Ford, Colson Whitehead and the tides of American fiction

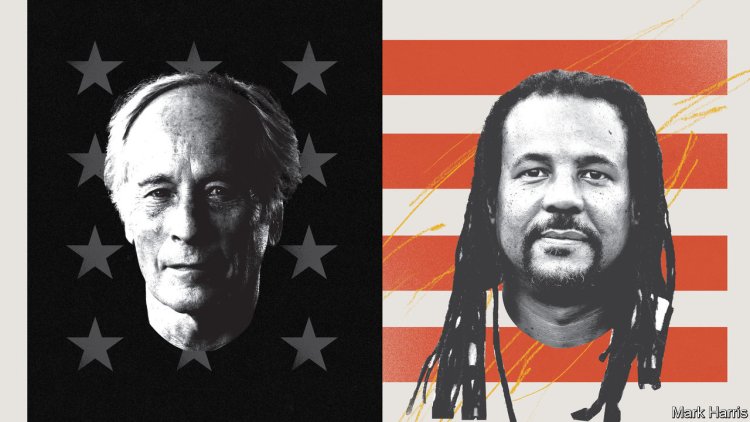

image: Mark HarrisBe Mine. By Richard Ford. Ecco; 352 pages; $30. Bloomsbury; £18.99Crook Manifesto. By Colson Whitehead. Doubleday; 336 pages; $21. Fleet; £20RICHARD FORD and Colson Whitehead are two of America’s most distinguished living novelists. Mr Ford (pictured left), who is 79 years old, has published eight novels and four short-story collections and won the Pulitzer prize once. Mr Whitehead (pictured right), 25 years younger, claims a pair of Pulitzers over his eight-novel career. The two have a colourful history: at a party nearly 20 years ago, Mr Ford, angered by Mr Whitehead’s negative review of his story collection, “A Multitude of Sins”, spat on the younger writer. (Mr Whitehead, who is funnier by far, warned “the many other people who panned the book that they might want to get a rain poncho, in case of inclement Ford”.) Both have new novels that reveal two strains of American fiction: one declining and the other thriving.Mr Ford’s is the moribund one. “Be Mine” is his f

Be Mine. By Richard Ford. Ecco; 352 pages; $30. Bloomsbury; £18.99

Crook Manifesto. By Colson Whitehead. Doubleday; 336 pages; $21. Fleet; £20

RICHARD FORD and Colson Whitehead are two of America’s most distinguished living novelists. Mr Ford (pictured left), who is 79 years old, has published eight novels and four short-story collections and won the Pulitzer prize once. Mr Whitehead (pictured right), 25 years younger, claims a pair of Pulitzers over his eight-novel career. The two have a colourful history: at a party nearly 20 years ago, Mr Ford, angered by Mr Whitehead’s negative review of his story collection, “A Multitude of Sins”, spat on the younger writer. (Mr Whitehead, who is funnier by far, warned “the many other people who panned the book that they might want to get a rain poncho, in case of inclement Ford”.) Both have new novels that reveal two strains of American fiction: one declining and the other thriving.

Mr Ford’s is the moribund one. “Be Mine” is his fifth book featuring Frank Bascombe, a wry, bemused observer of life, who is clearly indebted to John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom. Rabbit is the protagonist of a tetralogy that begins with him as a lusty 26-year-old still trying to live up to his high-school promise and ends with Rabbit moping around a Florida condo with a couple of grandchildren and a king-size case of ennui. Frank began literary life as a youngish sportswriter with a disintegrating marriage, one dead son and one living one; he ends it as a semi-retired real-estate agent, taking his remaining son, now dying from ALS, on one last trip, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, to Mount Rushmore.

Frank and Rabbit are both what were once called “everyman” characters. That word always revealed more about the assumptions of the person using it than about the book in question. Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, Updike’s rough contemporaries, also wrote first-person narratives in which men stumble, think and find their ways through the world, trying to square noble intentions with primal impulses. But they and their protagonists were Jewish, and therefore not everyman material in quite the same way as Rabbit is.

You could argue this was a blessing: it meant that Nathan Zuckerman, Augie March and other Roth and Bellow protagonists did not have to represent anything other than themselves. But it was also exclusionary. While Roth and Bellow wrote about Jews in America and contemporaries Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright about African-Americans, it was implied that novelists such as Updike and Mr Ford were somehow more purely American: only they could provide, as one reviewer wrote of Mr Ford’s first Bascombe book, a “CAT scan of the shell-shocked American psyche”. It is impossible to imagine a reviewer today deciding a single author’s perspective—particularly that of an ageing white man—stands in for all Americans.

And if Frank is just Frank, and not a stand-in for something larger, what is left? He is ironic and detached to the point of inhumanity. Paul, his son, dies in hospital while Frank is in the car listening to a baseball game. It leaves him unruffled, a reaction wholly unbelievable to any parent. (Mr Ford is childless, and it shows.) Paul, meanwhile, is immature and demanding. Novelists are under no obligation to make their protagonists likeable, but they should at least be interesting, which neither Paul nor Frank are.

That was not the case in previous books. Strangely, Frank’s wrestling with mortality and his observations about the world felt sharper in earlier books, when he was younger, than in this one. “Be Mine” is a dreary, dutiful slog—for both Frank and the reader. This is probably the last Frank Bascome book. Not only is Mr Ford nearly 80, but it gives little away to note that the book ends with a hint of dementia. He’s had a good run.

Mr Whitehead, meanwhile, represents a livelier and more expansive faction within American fiction. He uses some of the same tools as Mr Ford: like Frank Bascombe, the main character in “Crook Manifesto” is a serial protagonist. This book is a sequel, and structural copy, of “Harlem Shuffle” (2021)—both comprise three linked crime novellas set in Harlem, “Shuffle” in the 1960s and “Manifesto” in the 70s. Mr Whitehead is planning another Carney book, set in the 80s.

Carney owns a furniture store but also fences stolen jewellery. This duality gives Mr Whitehead ample opportunity for social commentary and observations about Harlem, which is really Mr Whitehead’s main subject, and New York more broadly. He writes about how the city is enduring yet constantly changing, how “atop the unchanging schist, the people replaced each other, the ethnic tribes from all over trading places in the tenements and townhouses, which in turn fell and were replaced by the next buildings.”

As for plot, Lee Child, author of the fantastically successful Jack Reacher series, said that in a crime novel, plot should function “like a rental car”, meaning it should be perfectly functional but not the main attraction. Character is the important thing, and these books succeed because readers care about Carney.

Still, Mr Whitehead takes plot seriously. At one time that may have been damnation with faint praise: literary writers were supposed to be above plot, which was the purview of genre writers. But the gap between genre and literary fiction has narrowed, and Mr Whitehead has long embraced both. He has incorporated horror (“Zone One”, which he published more than a decade ago, is perhaps the most urbane zombie novel ever written), fantasy (the animating conceit in “The Underground Railroad”), and legend, in “John Henry Days”, his second novel. Even his overpraised “The Nickel Boys” features a genre-esque plot twist.

On one hand, this is a welcome development. But behind this silver lining lies a cloud: literature’s diminished place in American life. Listing the newspapers that have ceased or shrunk their coverage of books would be prohibitively long. Literary and genre fiction are no longer rivals but partners, defending the same imaginative territory in the same shrinking foxhole. ■

What's Your Reaction?